Monday, June 29, 2009

Newport News Part II: The People

We arrived in Newport News in the evening only to discover that our hotel, the always popular for the budget conscience Super 8, was on the wrong side of the tracks. Literally. There were train tracks, and as far as we could tell, we were on the wrong side of them. The woman who handled our check-in at said Super 8, provided our first encounter with the supremely friendly Newport Newsians. She wanted to know all about why we were visiting Newport News, while at the same time telling us that the motel was unusually full thanks to a weekend jazz festival, and trying to ply us with brochures to area attractions such as Jamestown and Colonial Williamsburg, which we had no way to get to given our car-less situation. After insisting (at least three times) that yes, we would for sure call her if there was anything we needed once we got to the room, Erin and I settled in for our first night on the road.

The next morning, we arose bright eyed, bushy tailed, and more than ready to take on the Newport News public transportation system and the Mariners' Museum archives. A rather uneventful bus ride landed us at the front of Christopher Newport University, a lovely campus with a spectacular library where the Mariners' Museum archive is housed. Upon arriving at the campus, Erin and I asked one of the people working on the summer landscaping if she could point us in the direction of the library. The woman did us one better and got her companion to drive us right to the library in his golf cart. This ride, while welcome, was slightly uncomfortable as all three of us were squished into the front seat due to the plants that were occupying the back area of the vehicle.

Once we were deposited at the library, Erin and I were able to quickly make our way to the archive, where we met Mr. Bill Edwards-Bodmer, the library researcher. Mr. Bodmer turned out to be a lovely person and a great help to our project. He provided us with a list of all of the library's piratical materials and was more than happy to let us look at anything we wanted to. He even gamely put up with our very un-library appropriate excitement over the many editions of Exquemelin's Buccaneers of America and constant habit of reading especially good bits of what every document we happened to be working on out loud.

The seven hours we spent in the Mariners' Museum archive that day passed by in the blink of an eye and Thursday evening found Erin and I wandering the grounds of the Mariners' Museum itself. During our exploration, we stumbled upon a lake where we were presented with the opportunity to set sail in a pirate paddle boat for $5 per half hour. Given the subject of our research, how could we refuse? Erin and I quickly boarded our craft after the wonderful paddle-boat people snapped a photo which can be seen here. Our trip took us past charming bridges, mysterious coves, and a really oddly shaped tree. We briefly entertained the idea of trying to take the other paddle boat on the lake as a prize, but lack of speed and any real navigational talent persuaded us not to proceed in this endeavor.

Paddle boating is hard work, and after this adventure Erin and I decided that it was time to hunt down some victuals. The first restaurant we came across was the Warwick Restaurant, a local diner which provided us with a truly unique and entertaining dining experience. The meal began with a perusal of our menus where it was stated that with our entree we would have our choice of two vegetables. The veggie choices were as follows: mashed potatoes, french fries, potato salad, cole slaw, apple sauce, pickled beets, baked potatoes, and "vegetable of the day", which turned out to be collared greens. The experience only got better from there. Our waitress was a fabulous woman who took our order in an exceptionally friendly manner, and then proceeded to ask if we had hear about the death of Michael Jackson. Since Erin and I had been holed up in the library all day, this was news to us, and we had a nice bonding moment as the three of us commiserated over the loss of the controversial legend. Our waitress then proceeded to personally break the sad news to every other individual table in the diner, and soon a restaurant wide discussion of Michael Jackson ensued. After learning some valuable lessons about life, death, and the importance of cable television from the locals, Erin and I called it a night and headed back to the Super 8.

Once we reached the hotel, we quickly realized that our room keys had been demagnetized and I headed downstairs to get them fixed. Our friend from the night before was once again manning the desk and was more than happy to help me. She was thrilled that Erin and I seemed to be enjoying our stay in Newport News. The highlight of our conversation came right as I was about to head upstairs when she called after me with the words, "Child, do you know that Michael Jackson passed?". And on that rather odd note, our first and only full day in Newport News ended.

The next morning passed much in the same fashion as the first, with a bus ride and hours spent buried in the Mariners' Museum archive feverishly trying to work our way through all of the great pirate resources available to us before our inevitable trip back to DC. Erin and I quitted the library, in sort of a dazed state of pirate overload later in the afternoon. We made it safely to the Amtrak station where we boarded our train back to the big city and proceeded to spend our journey refusing to read, or even look at anything with the word "pirate" in it.

So ends our great adventure in Newport News. Stay tuned for the next installment of our travels, detailing what is sure to be a thrilling expedition to Boston and Mystic Seaport!

Newport News Part I: The Archives

I won't subject you to all of the many wonders included in works such as: Mutiny and Murder- Confession of Charles Gibbs: a native of Rhode Island- Who, with Thomas J. Wansley, was doomed to be hung in New-York on the 22nd of April last, for the murder of the Captain and Mate of the Brig Vineyard, on her passage from New Orleans to Philadelphia in November 1830. Gibbs confesses that within a few years he participated in the murder of nearly 400 human beings! or A Most Wonderful Providence, In Many Incidents at Sea: An Engagement with a Pirate and a Mutiny at Sea, of Board Ship Ann of Boston, Commanded by Captain Eliah Holcomb: Written By Himself, And to the Truth of which he is willing to qualify at any time. Instead, I will be treating you to a cliffnotes version of my most interesting findings.

Because most of the documents that I read were all published around the same time, the first half of the 19th century, I was able to notice several interesting continuities between the ways in which pirates were portrayed in each of the works. As Erin pointed out in her earlier post, pirates and privateers were viewed as something akin to national heroes in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Well, let me tell you, by the time the 1800s rolled around there were no references to the "Heroick exploits of our own Countrey-men, and Relations". Instead, the forces of Victorian era were in full swing and a pirate was much more likely to be described as, "an active participator in the commission of crimes that are stamped with the most shocking barbarity!" (a particular gem taken from the trial of Charles Gibbs).

The accounts of trials and executions that I read were probably one third actual fact, one third sensationalized fiction, and one third warnings against the complete moral depravity of piracy. The authors seemed to relish reporting the heinous crimes committed by these pirates. For example, during the trial of Charles Gibbs, the pirate was reported to have recounted the following passage relating to the treatment of the crews belonging to ships captured by pirates:

"...as soon as we got a ship's crew in our power, a short consultation was held, and if it was the opinion of a majority that it would be better to take life than to spare it, a single nod or wink from our captain was sufficient-- regardless of age of sex, all entreaties for mercy were then made in vain-- we possessed not the tender feelings to be operated upon by the shrieks and expiring groans of the devoted victims!-- there was rather a strife among us, who, with his own hands, should dispatch the greatest number, and in the shortest period of time."It was also impossible to miss the religious undertone that ran through almost all of these accounts. A plan to mutiny that resulted in the death of the captain and and several officers aboard the Plattsburg in 1816 was described in the following words: "...which, from its diabolical nature, we think ourselves warranted in saying, must have had Lucifer for its projector!", and the judge in the Charles Gibbs case followed his sentence of death with the advice that the convicts should use their time in prison to "seriously think and reflect on their FUTURE STATE!".

The authors of these pamphlets also took every opportunity to issue "Solemn Addresses to Youth" in order to entreat upon the youngsters of America to never turn to piracy as a means of seeking their fortune. All of these addresses cautioned youth to show "filial respect" to their parents and act wisely in "choosing your connexions". Above all though, these addresses stressed the merits of virtue and the necessity of this trait in living a successful, fulfilling life (or in other words, one that doesn't end with a trip to the gallows).

I think that this poem included at the end of The Pirates- A brief account of the HORRID MASSACRE of the Captain, Mate, and Supercargo of the Schooner Plattsburg of Baltimore, on the High Seas in July 1816 By a part of the crew of said vessel really sums up the spirit of my findings quite nicely.

Written on the Condemnation of the Pirates

How my heart with bitter anguish

Sinks in melancholy gloom;

Pensive and sad my muse must languish

As I sing the Murderer's doom.

Lo! In gloomy cells confined,

Shut from light and wholesome air,

Are four Outlaws, in chains entwined,

Who must for speedy death prepare.

All moral ties they burst asunder,

No laws could these vile wretches bind;

For nought but murder, guilt, and plunder,

In their vile hearts could refuge find.

As on Ocean, in soft slumber,

Three devoted victims sleep;

Ah! their hours are few in number,

Soon they're destined for the deep!

Ere the midnight watch is called,

Sudden alarm is quickly spread;

The victims rise- they are enthralled,

Soon to be numbered with the dead.

Cruel ruffians now surround them;

In vain for mercy do they cry;

With heavy blows the fiends astound them;

All hope has fled- alas!-- they die!

But what a final retribution

Soon the murderers will await;

Speedy, for their vial pollution

Will the wretched meet their fate.

Let our youth by them take warning;

Shun the path those murd'rers trod--

Lest, they should be by virtue scorning,

Call'd to the awful bar of God.

Channeling Indiana Jones in the Mariners' Museum archives

1684: Exquemelin's account was presented as an exhortation to the bold and adventurous English national spirit in the face of the devious Spanish. From the Translator's Note to the Reader:

The present Volume, both for it's [sic] Curiosity, and Ingenuity, I dare recommend unto the perusal of our English Nation, whose glorious Actions it containeth ... and besides, it informeth us (with huge novelty) of as great and bold attempts, in point of Military conduct and valour, as ever were performed by mankind; without excepting, here, either Alexander the Great, or Julius Ceasar, or the rest of the Nine Worthy's of Fame ... We having here more than half the Book filled with the unparallel'd, if not unimitable, adventures and Heroick exploits of our own Countrey-men, and Relations; whose undaunted and exemplary Courage, when called upon by our King and Country, we ought to emulate.To be clear, the "Countrey-men" in question include, most notably, Captain Henry Morgan, perhaps best known for his brutal attacks on Maracaibo and Panama that left hundreds of men dead and entire towns burned. In the preface to the second volume (Containing The Dangerous Voyage and Bold Attempts of Captain Bartholomew Sharp, and others; performed upon the Coasts of the South Se, for the space of two years, &c. From the Original Journal of the said Voyage. Written by Mr. Basil Ringrose, Gent. Who was all along present at those Transactions.) the anonymous publisher addresses apparent inaccuracies in Exquemelin's account of Morgan's burning of Panama thusly:

And what disgrace were it, to that worthy person, if he had set fire unto it, for those reasons he knew best himself? Certainly no greater dishonour than to take and plunder the said City. Thus are these persons so far transported with passion towards Sir Henry Morgan, as to bereave him of the glory of his greatest Actions, whether true or false ... Thus both the English Nation, and the Spanish having agreed, to give the honour of this Action either truely or falsely, unto Sir Henry Morgan, I cannot but admire those who pretend to be the greatest admirers of his merits, should endeavour to devest him of it.1699: The preface to the 1699 edition echoes the 1684 admiration of Morgan and the buccaneers, but it is more qualified than the earlier praise, providing a glimpse of the characterization of pirate as immoral savages that will later become dominant in the pirate narrative:

It would be superfluous to say much by way of Preface to the following Work, since a great part of it has some Years ago been Exposed to Publick view with a general Applause; and indeed the wonderous Actions and daring Adventures therein related, are such as could not but transport the most stupid minds into an Admiration of them, tho many times they were not attended with that Justness and Regularity that became Christians, or even men of any Tolerable Morals.However, the passage from the 1699 edition that caught my attention most acutely (which is a professional way of saying that I lept up from the table and shouted in excitement) was as follows:

I will not take upon me to Apologize for many of the Actions done, and here related, since even in the most regular Troops and best disciplined Armies, daily Enormities are committed which the strictest vigilance cannot prevent; However it is very remarkable, that in such a lawless Body as these Bucaniers seemed to be, in respect to all others; that yet there should be such an Oeconomy (if I may so say) kept and regularity practiced among themselves, so that every one seemed to have his property as much secured, as if he had been a member of the most Civilized Community in the World; tho at the same time when I consider of some of their Laws, such as those against Drunkenness and the like immoralities, I believe I have a great deal of reason to remain suspicious of their Sincerity. But be these things as they will; a bolder Race of Men, both as to personal Valor and Conduct certainly never yet appeared on the liquid Element, or dry Land; and I hope it will be taken neither for an Affront nor a Complement, to say the English were always the leading and prevailing party amongst them.This passage represents an elegant distillation of so many pirate tropes (some abandoned, others still very much around) that I could hardly sit still. In it we have not only the distinction between pirates and the "civilized world" that later became so dominant, but also an appeal to the greatness of the English identity, and, perhaps most remarkably, a 17th century nod to the political economy of piracy that so fascinates Peter Leeson today. Incredible!

1741: But the plot thickens! The next edition the library had was one from 1741. It appeared to have the identical preface to that of the 1699 edition but on closer examination I noticed that the phrase that read "tho at the same time when I consider of some of their Laws, such as those against Drunkenness and the like immoralities, I believe I have a great deal of reason to remain suspicious of their Sincerity" was entirely gone from this edition, thereby significantly strengthening the preface's (non) apology for piratical atrocities. It's worth noting too that the earlier appeals to English nationalism were well intact, and that the 1741 publication date occurred not insignificantly right in the middle of the English War of Jenkins' Ear against their old enemies the Spanish and which had included, in 1739 a state-based capture of Porto Bello, Panama by the British navy.

1856: The 1856 American edition of Buccaneers is most notable for its distancing of the contemporary world from the piracy of old. Piracy here is presented as an historical phenomenon. The 1856 edition kept the 1699 preface (and the line about being suspicious about the sincerity of pirate codes has made a miraculous return), but added an introduction lauding the civilized age in which its readers lived:

Read the following pages, and compare the state and transactions of the world at the times on which it treats with those of the present. If, when they have done this, they are not satisfied that the general character of mankind has been greatly ameliorated within the last three centuries, nothing, it is thought, would satisfy them of the fact... there has been a complete revolution of the seas. Sea-kings are no longer known or acknowledged ... it is only necessary to survey our own American coast within the space of two hundred years after its settlement by Europeans, to learn what terrors awaited all those who attempted voyages by sea.By now, the perception of pirates as dangerous and acting well outside the bounds of acceptable behavior is well in place -- a startling contrast with the hero-worship of the same actions from a century before. We've gone from references to "the valour of our famous Bucaniers" (1684 translator's note) to stating that "the records of our admiralty courts are full of trials of pirates, with the most revolting accounts of their cruelties and their executions."

1891: This edition was the second one which led me to jump up and exclaim aloud, so incredible a find was its introduction by editor Howard Pyle. Listen to how it begins:

Why is it that a little spice of deviltry lends not an unpleasantly titillating twang to the great mass of respectable flour that goes to make up the pudding of our modern civilization? And pertinent to this question another -- Why is it that the pirate has, and always has had, a certain lurid glamour of the heroical enveloping him round about?As early as 1891, Pyle was asking (in unfortunately purple prose) some of the same questions we were about the romanticization of piracy! And he goes on:

Is there, deep under the accumulated debris of culture, a hidden ground-work of the old-time savage? Is there even in these well-regulated times an unsubdued nature in the respectable metnal household of every one of us that still kicks against the pricks of law and order? To make my meaning more clear, would not every boy, for instance -- that is every boy of any account -- rather be a pirate captain than a Member of Parliament? And we ourselves; would we not rather read such a story as that of Captain Avery's capture of the East Indian treasure-ship, with its beautiful princess and load of jewels ... than -- say one of Bishop Atterbury's sermons or the goodly Master Robert Boyle's religious romance of "Theodora and Didymus? It is to be apprehended that to the unregenerate nature of most of us, there can be but one answer to such a query.It's not that Pyle's answers to these questions are convincing or even entirely helpful to our research program, but the fact that he thought to ask them indicates a fascinating degree of self-awareness -- even 100 years ago -- of the grip piracy held on the popular imagination. Too, Pyle provides a wonderfully clear and detailed articulation of what "pirate" meant at the end of the 19th century:

Courage and daring, no matter how mad and ungodly, have always a redundancy of vim and life to recommend them to the nether man that lies within us, and no doubt his desperate courage, his battle against tremendous odds of all the civilized world of law and order have had much to do in making a popular hero of our friend of the black flag. But it is not altogether courage and daring that endears him to our hearts. There is another and perhaps a greater kinship in that lust for wealth that makes one's fancy revel more pleasantly in the story of the division of treasure in the pirate's island retreat, the hiding of his godless gains somewhere in the sandy stretch of tropic beach, there to remain hidden until the time should come to rake the dubloons up again and to spend them like a lord in polite society, than in the most thrilling tales of his wondrous escapes from commissioned cruisers through tortuous channels between the coral reefs. And what a life of adventure is his to be sure! A life of constant alertness, constant danger, constant escape! An ocean Ishmaelite, he wanders for ever aimlessly, homelessly; now unheard of for months, now careening his boat on some lonely uninhabited shore, now appearing suddenly to swoop down on some merchant-vessel with rattle of musketry, shouting, yells, and a hell of unbridled passions let loose to rend and rant. What a Carlislean hero! What a setting blood and lust and flame and rapine for such a hero!

During the early eighteenth century the Spanish main and adjacent waters swarmed with pirate crafts, and the fame of their deeds forms a chapter of popular history that may almost take rank with that which tells of Robin Rood, Friar Rush, Schinderhammes, and other worthies of the like kidney of a more or less apocryphal nature. Who has not heard tell of Blackbeard? Who does not know of the name of the renowned Captain Kid? Who has not heard the famous ballad which tells of his deeds of wickedness?The introduction is quite lengthy and dominated by the twin themes of "savagery" ("Among the buccaneers were to be found the off-scourings of all the french and English West Indies -- a mad, savage, unkempt phase of humanity, wilder than the wildest Western cow-boys -- fierce, savage, lawless, ungoverned, ungovernable") and "blood" ("In ten or twelve years Spain had lost millions upon millions of dollars, which vast treasure was poured in a golden flood into those hot fever-holes of towns, where Jews and merchants and prostitutes battened on the burning lusts of the wild hunters whose blood was already set aflame with plunder and rapine"), repeated over and over again. Finally, Pyle's explanation of why he has kept the original translation of Buccaneers largely intact bears repeating:

One touch of the modern brush would destroy the whole tone of dim local colours of the past made misty by the lapse of time. It needs the quaint old archaic language of the seventeenth century to tell of those deeds of blood and rapine and cruelty, and the stiff, formal style of the author-translator seems in some way to remove those deeds out of the realms of actuality into the hazy light of romance. So told the adventures of those old buccaneers still remain a part of humbler history, but they do not sound so cruel, so revolting as they would be told in our nineteenth-century vernacular.Incredible! The temporal distancing that is evident beginning with the 1741 edition, but most notably in the 1856 one is self-consciously and deliberately articulated here.

1924: The 1924 edition includes a remarkably awful introductory essay by Andrew Lang, noteworthy first of all for its Cordingly-like approach to the putative gap between the "romance" and "reality" of piracy:

Most of us, as boys, have envied the buccaneers ... The buccaneers is 'a gallant sailor,' according to Kingsley's poem [Canon Kingsley, "The Last Buccaneer"] -- a Robin Hood of the waters, who preys only on the wicked rich, or the cruel and Popish Spaniard, and the extortionate shipowner. For his own part, when he is not rescuing poor Indians, the buccaneer lives mainly 'for climate and the affections'... Yet the vocation [!] was not really so touchingly chivalrous as the poet would have us deem ... The buccaneers were certainly models of diligence and conscientiousness in their own industry, which was to torture people till they gave up their goods, and then to run them through the body, and spend the spoils over drink and dice ... they were the most hideously ruthless miscreants that ever disgraced the earth and the sea.The second element of note in Lang's essay is the unremittingly negative light in which the buccaneers are portrayed and his efforts to warn youth that "pieces of eight do not grow on trees." This compulsion to warn youth against the temptations of piracy is something that Catherine noted in much of the reading she did, especially in sensationalist 19th century accounts of the lives and trials of some famous pirates, but I'll let her tell about that.

The various editions of Buccaneers of America were not the only readings I did at the Mariners' Museum -- Catherine and I read and took notes through a fairly impressive collection of piracy-related documents -- but this post has gone on for far too long, so I think I'll wax enthusiastic over such masterpieces as The Life, Trial, Confession and Execution of Albert W. Hicks, The Pirate and Murderer, Executed on Bedloe's Island, New York Bay, On the 13th of July 1860, For the Murder of Capt. Burr, Smith and Oliver Watts, on Board the Oyster Sloop E.A. Johnson. Containing the History of his Life (Written by himself) from childhood up to the time of his arrest. With a full account of his piracies, murders, mutinies, high-way robberies, etc., comprising the Particulars of nearly One Hundred Murders another time.

To conclude, here is a picture of Catherine and I with our trusty pirate-themed pedal boat (ahem, hijacked sloop) at the lake outside the Mariners' Museum after a long day in the archives:

Real pirates always wear their life jackets. For further photo documentation of our trip (and an unwarranted number of pictures of trains and Leifr Eiriksson) click here.

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

Something for everyone!

For the military technology geek: The Vienna-based company Schiebel Group, known for its work with mine-detection and UAV technology is, as Danger Room notes, advertising a robotic helicopter as a pirate detection system.

The three-year-old Camcopter design is popular with organizations working to “de-mine” old battlefields, and with oil companies, for pipeline monitoring. But the 10-foot-long, 200-pound bird, can also be flown from tankers and other large vessels, in order to search ahead for pirates, according to Schiebel. The company told Aviation News, in June, that a Saudi tanker operator has already “shown interest” in buying Camcopters for Somalia duty. But it’s worth noting that the US Coast Guard stresses alert watchmen, sailing fast, and pulling up a ship’s ladder — not some expensive technology – as the best methods for beating pirates.For the type of people who read the Foreign Policy blogs every morning: Japan's parliament has authorized the use of force by the Japanese Navy against Somali pirates, raising more questions about the future of Japan's pacifist constitution.

For people interested in international maritime law: A NATO warship recently captured a group of pirates who tried to hijack a Singaporean freighter, stopping the hijacking with no casualties but later releasing the pirates. NATO has been criticized before for being too gentle with captured Somali pirates, and the organization does not have a detainment policy; the arresting warship must follow its own national laws.

For readers of biography: The Providence Journal published a biographical sketch of Thomas Tew, a late 17th century pirate and privateer, who operated off the coast of Africa, raiding Mughal ships. Probably.

In the 17th century there was a pirate from Rhode Island. Or perhaps he was a privateer. Maybe he wasn’t from Rhode Island after all. These are the kind of “facts” that float to the surface when one stirs the murky brew of hand-me-down history that has fermented for centuries, from a time when legend often was prized over fact, and records, if kept, have crumbled to dust.As Catherine noted the other day, however, the beauty of our project is that it doesn't actually matter who Tew really was or what he really did. Intersubjective understandings and cultural representations of piracy are based on myth-making. What's interesting here is the continued interest in Tew's roguish deeds -- not whether Tew actually did them.

For the history buff: There's a movement afoot in Scottish Parliament to clear Captain Kidd's name following research that indicates that Kidd may have been framed by King William III, "who wanted to appear tough on piracy but who also stood to profit from the goods which Kidd seized." The tale of Kidd's hanging is pretty grisly -- the rope snapped the first two times -- and his body was tarred and hung along the banks of the Thames as a warning. The Scottish MP behind the motion has cast it in terms of justice, noting the problematic ambiguity of the privateer/pirate distinction:

"I think these types of incidents, whenever they happen, have a lesson and a morality for all time because otherwise we allow people to get away with breaking the law and breaking rules and we allow governments to get away with punishing people wrongly. I don't expect that there's going to be a mass campaign in the streets for something that happened 300 years ago but I do expect that people are going to be worried about the fact that someone can be used and abused in that way by the state, whatever time in history. If someone is accused and hung for something that he didn't actually do, when he was operating for the government and he was doing the job properly, that comes down to a criminal act on the part of the government not on him."For the local TV viewer like you: The Discovery Channel and the Military Channel recently aired a program on the capture and rescue of the captain and crew of the Maersk Alabama, with a local man from Norfolk, VA playing the role of Abduwali Abduqadir Muse, the accused pirate awaiting trial in New York.

Monday, June 22, 2009

Piratz!

The waitstaff were all dressed in true pirate style with leather boots, three cornered hats, billowing shirts, striped pants, and velvet jackets. The women were wearing gowns with appropriately large amounts of cleavage bared and patrons at the bar were allowed to tip by putting dollars...well, I'm sure you can guess where. The drinks (which unfortunately Erin and I are not old enough to partake of) were all fruity concoctions or full of potentially lethal amounts of rum.

Erin and I also had the singular good luck of being at Piratz the same night as a troupe of pirate actors known as The Vagabonds. From what we could gather based on conversations with a couple members (who were very happy to chat after hearing about our research) these people are masters of pirate history, weaponry, and culture. One man is a fight choreographer who lost sight in one eye during a practice duel, and if that's not hard core, I'm not entirely sure what is. Erin and I bonded with one pirate in particular after he teased us for being sober and pronounced our lack of fake IDs as truly against the pirate lifestyle. The Vagabonds were at Piratz Tavern to provide the evening's entertainment which took the form of pirate drinking songs and chanteys, some of which required audience participation, and most of which were well past PG in content.

Now the thing is, neither Erin nor I are "pirate people". I was not the kid who lived for treasure hunts and begged my parents for toy swords at Christmas. As a high schooler, I was not the girl who could quote lines from Pirates of the Caribbean verbatim and had a life size cardboard cut out of Johnny Depp in my bedroom. My favorite ride at Disney Land was so Splash Mountain, and I have felt no compulsion to change my facebook language settings to pirate. In fact, Erin and I have actively resisted becoming pirate people, partly because we like to actively resist things, but mostly because we don't want it to give the appearance we decided to do this project because "pirates are awesome!" or something... Even so, the evening at Piratz Tavern was a lot of fun. It was nice to leave the academic focus of our research behind for the night and let ourselves enjoy the cheesy, cliched, and more than a little ridiculous side of things. Just as the Piratz Taveren website advertises, it was most certainly an "escape from the ordinary"!

Dissent! Dissent on the pirate blog!

If all of these boundaries are contested and contingent, the question is, How are they produced and reproduced such that they appear permanent, fixed, and natural? Why do we think we know what sovereignty is? Put differently, how are Ruggie's 'hegemonic form of state/society relations' or Ashley's 'hegemonic exemplar' of 'a normalized sovereignty' constructed? (18)Thomson recognizes that sovereignty is variable, social, and contingent (12-13) but rather than treating discourse as a constitutive site of sovereignty, she discounts it entirely as such:

Textual (intertextual, contextual) interpretation, discourse analysis, and other deconstruction methods are not the necessary or only alternative. It is not clear that these methods will generate a 'productive' research program in the Keohanian sense ... Moreover, by adopting such unconventional methods, critical theory allows or forces mainstream scholars to dismiss postmodernism based on its research designs, methods, and data. It hardly helps matters that much of postmodernist discourse is opaque (thus, largely meaningless) to ordinary international relations scholars ... Beyond this, the postmodernist focus on discourse poses the danger of diverting attention from the reality of state power to the discourse about it. States are now massive, physical, bureacratic, and coercive institutions that have been developing for some six centuries. While postmodernists are surely right to claim that discourse is the deployment of power, it is implausible to argue that the exercise of power in this form is of central importance to, much less decisive in, world politics. Discourse may contribute to the construction of the state but I am not convinced that the state might be fundamentally altered if the discourse on the state changed or that it would vanish if we stopped talking about it. (161)These are pretty damning charges that strike at the heart of our research project, especially given the overlap between the construction of sovereignty and the construction of pirates, that Thomson herself observes and analyzes (hence the book's title). My response* to this footnoted assault on my summer's work, then, is four-fold:

1. Thomson questions whether discursive analyses can generate a productive research program, citing Robert Keohane's critique of reflectivism in "International Institutions: Two Approaches." However, Thomson herself, writing in 1994, dismisses this critique on empirical grounds in an earlier footnote, noting that "this charge is unfair to the extent that these scholars have spawned the deconstructionist project in international relations" (160). Fifteen years later, the empirical argument against claims of "no research agenda" is even stronger. IR scholars such as Jutta Weldes, Charlotte Epstein, Neta Crawford, and Janice Bially Mattern have written post-structuralist analyses that explicitly focus on discourse and rhetoric using a coherent and rigorous --if unapologetically non-positivist -- methodology. The theory and methodology informing such works present an implicit research model, and in Security as Practice: Discourse Analysis and the Bosnian War, Lene Hansen offers an explicit description of how to conduct quality discourse analysis research. Works like Dvora Yanow and Peregrine Schwartz-Shea's Interpretation and Method: Empirical Research Methods and the Interpretive Turn represent contemporary attempts to develop a set of serious guidelines around which to orient such textually focused research methods.

As for Thomson's charge that such "unconventional" methods force mainstream scholars to dismiss such research, again, that is a norm that is changing, and articles such as the extended exchange in International Studies Quarterly between Robert Keohane (!) and J. Ann Tickner (see here and here and here and here) indicate that conventional scholars are indeed seriously engaging with non-mainstream methods, even as they critique them.

Next, it is unclear to what extent Thomson herself follows a clearly defined "productive" research program. Her rejection or realist and liberal assumptions about sovereignty puts her squarely outside the realm of mainstream IR theory, and her use of an interpretive institutionalist "protoparadigm" (14) seems open to much the same critique that she levels at postmodernism.

2. Thomson states that postmodernist discourse tends to be incomprehensible to IR scholars. First of all, the arguments above about how unconventional methodologies are theories are becoming increasingly conventional applies here. Second, I would suggest, that this is a relatively silly, red herringish, reason to dismiss such methods. I'm sorry they are difficult to understand, but a methodology that dismisses parsimonious covering laws is bound to be a bit complicated. I'm sorely tempted to say that this criticism has nothing to do with the merits of postmodernist methods, but I'm afraid it would be obnoxiously hypocritical to exempt postmodernist discourse from a critique of postmodernism. A better response is that every discipline has its vocabulary and Thomson's book -- particularly her theory and method chapter -- would be quite difficult to the policy-makers whom she briefly addresses in the final chapter (151-152) if they had no knowledge of academic IR theory. The best response would be to not prejudge the question; we have no intention of gratuitously using esoteric academic jargon -- from any discipline -- in our paper and to the extent that we do, we intend to clearly and concisely define our terms (or at the very least, present an argument for why we don't).

3. Thomson's argument that focusing on discourse about power takes attention away from "the reality of it" is powerfully discounted by every one of the rhetorically-focused constructivist authors whose theory and methods we draw upon in our research. Such authors argue that discourse and policy are mutually constitutive: that there is no brightline between discourse and reality. In "Twisting Tongues and Twisting Arms: The Power of Political Rhetoric," for example, Ronald Krebs and Patrick Thaddeus Jackson outline a particular mechanism (that of rhetorical coercion) by which state power can be discursively deployed. Further blurring the putative line between rhetoric and reality, Jutta Weldes explains how official discourse shapes the national interest and creates the conditions of possibility under which force can and cannot be deployed:

Drawing on and constrained by the array of cultural and linguistic resources already available within the security imaginary, state officials create representations that serve, first, to populate the world with a variety of objects, including both the self (that is, the state in question and its authorized officials) and others ... Second, such representations posit well-defined relations among these diverse objects. These relations often appear in the form of quasi-causal arguments such as ... the domino theory ... Finally, in providing a vision of the world of international relations— in populating that world with objects and in supplying quasicausal, or warranting, arguments— these representations have already defined the national interest.Weldes argues that examining state discourse helps understand why claims about national interest and threats to state power are believed and thus legitimate state action, using the discursive construction of the Soviet deployment of missiles in Cuba as a "crisis" as a case study. In a similar tradition, Janice Bially Mattern makes the case in Ordering International Politics: Identity, Crisis, and Representational Force that language power is every bit as "real" as military strength and that representational force (what she calls a "threat of potential violence to the victim's subjectivity") can coerce "real" state action just as effectively as the traditional mechanisms of power politics. Specifically, she argues that the mechanisms of language power and rhetorical links between concepts like "betrayal" and "Dulles" made it impossible for the US to intend to use force against British cooperation with the nationalization of the Suez Canal.

Arguments like these demonstrate that discourse is indeed deeply relevant and even decisive in the exercise of world politics. To bring the discussion back to pirates, the fact that the United States can call the Somali hijackers "pirates" makes possible and rules out specific military and non-military reactions to what can be constructed as a threat. It's not as simple as labeling anyone the Navy SEALS want to snipe as a "pirate" -- prior understandings of the word determine whom we can label as a pirate -- but the deployment of the term itself does legitimate "real world" responses.

4. Thomson's final point here is that nothing would change if we altered our discourse on the state and the state would not vanish if we stopped talking about it. In response to the first half of the statement, the above argument applies fairly well. Again, because our use of discourse analysis rests on intersubjective understandings of various rhetorical commonplaces, we are not making the argument that a change in discourse can cause a change in state (or non-state) identities. The causal relationships we are analyzing are not one-directional independent-variable/dependent-variable type mechanisms. Rather, they deal with conditions of possibility and contingent configurations: because we understand a "pirate" to be someone who hijacks ships in international waters (to use a crude definition) based on a series of historical experiences, we can then deploy the term "piracy" to what we understand some Somalis to be doing in the Gulf of Aden. Then, because the term "piracy" carries with it a history of sanctioned state responses, we can respond "appropriately."

Thomson is correct; a deliberate and unilateral (or, I would argue, exclusively academic) change in state discourse -- in and of itself and devoid of the social context that gives it meaning -- would not inevitably change our understanding of the state. But, a change in the discourse about states that resonates with the public or that makes use of rhetorical coercion or deploys representational force -- such a shift in discourse could well change our understanding of states. States, to misquote Wendt, are what states make of them, but states cannot be made infinitely many things.

Thomson's claim that the state would not vanish if we stopped talking about it is a similar sort of perversion of (our flavor of) constructivist thought. It's a silly argument, because in today's political and international context we could not just decide to stop talking about the state. That's why all this constructivist talk of context and intersubjectivity matters; the state-based international system may be a social construction, but, as Thomson notes, we function as though it were real. Discourse does not independent produce or cause the state any more than the state independently produces or causes discourse. Discourse and the state exist only in relation to each other.

Epilogue: Finally, Thomson is correct that the knee-jerk reaction to the label of "postmodernism" by a certain, often generationally-defined, segment of academia (my father, for example) tends to be outright dismissal. Indeed, by labeling all textual and discursive analyses as postmodern, Thomson herself manages to confound theory and method and throw baby and bathwater out the window. Discourse analysis, of course, is a methodological tool that can be used to serve different theories and what Catherine and I are doing is actually constructivist rather than postmodernist in intention, to the extent that our concern lies much more with explicating contingent conditions of possibility and turning points than with revealing hidden structures of violence. But that would have been the easy response to all this and sometimes my own buried identity as a policy debater with eightminutestofillwithrapidfirespeechandnodroppedargumentsontheflow is revealed (I had to work very hard not to type TURN! before the third paragraph of subpoint 1) ...

*Maybe a footnoted methodological criticism doesn't really deserve an extended line-by-line rebuttal. On the other hand, maybe it really, really does. I adhere to the latter position. Additionally, I expect this will come in handy for our lit review.

Sunday, June 21, 2009

Threat of piracy ballooning off Africa's eastern coast

http://www.marriedtothesea.com/061109/somalian-balloon-pirate.gif

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Reporting live from Puntland

The first part takes a look at the Puntland region and the conditions that originally facilitated piracy as a business and continue to fuel it today:

Part 2 examines the system of hostages and ransom payments inherent in piracy, and Adow documents local reactions -- and objections to -- piracy in the town of Eyl.

BBC's Africa correspondent Andrew Harding also visits Puntland to report on the fight against piracy in Somalia:

Meanwhile, anti-piracy efforts continue apace outside Somalia as well. Interpol is currently working on compiling a database of Somali pirate suspects:

"Without systematically collecting photographs, fingerprints and DNA profiles of arrested pirates and comparing them internationally, it is simply not possible to establish their true identity or to make connections which would otherwise be missed," Interpol's Executive Director of Police Services, Jean-Michel Louboutin, said in a statement released Wednesday at the agency's headquarters in Lyon, France.

Monday, June 15, 2009

Sunday, June 14, 2009

Piracy as the high-profile tip of the Somali iceberg

John Boonstra, from UN Dispatch, would perhaps approve of this interest to the extent that it ultimately draws attention to Somalia's growing humanitarian crisis, which has resulted in over 100,000 internally-displaced persons. Boonstra quotes Italian Foreign Minister Franco Frattini:

"Piracy is only the tip of the iceberg," Frattini said. "We are convinced that piracy is related to the political and socioeconomic crisis on land, not on the sea.Boonstra notes, however, that the iceberg is "much, much bigger" than current steps (calls for international coordination, the establishment of pirate courts, and a Somali coast guard) are addressing, and he states that, "Compared with the widespread travesties faced by these thousands of Somalis, the international community's focus on piracy, whatever its impact on the global economy, seems almost an affront to human dignity. " But as Frattini's statement hints at, continued interest in the region and the piratical tip of the iceberg -- whether expressed in respected news media, the blogosphere, or Hollywood -- carries the possibility of increased awareness of the wide-spread human rights violations, violence, and war crimes. Given that the Somali pirates continue to hold a large number of vessels and appear to be expanding their range of attacks to the Persian Gulf, piracy is likely to stay popular in the news and culture, but whether the attention given to Somali's humanitarian problems will go beyond the following prerequisite cursory nods remains to be seen:

- "Somalia has been without a stable government since 1991, allowing piracy to flourish." (BBC)

- "The pirates in the recent string of attacks are all from Somalia, an extremely poor African country that hasn't had a stable government in decades." (Washington Post)

- "Piracy has become a multimillion-dollar business in Somalia, a nation that has limped along since 1991 without a functioning central government." (The New York Times)

Saturday, June 13, 2009

"Murdered by pirates is good!"

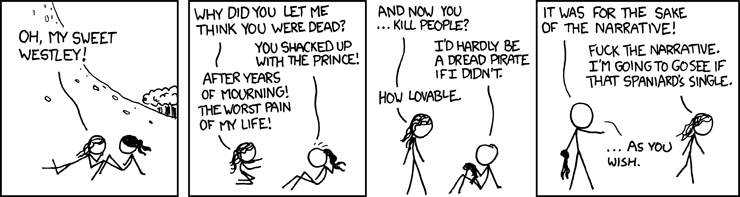

Also, because I cannot resist the pairing of narrative, pirate, and the Princess Bride, xkcd brings us:

*Actually, for geneaological purposes, Variety Pirate Theater 3000 (as one friend has termed it) will proceed in chronological order beginning with the 1921 silent film The Sea Lion. The Princess Bride was mostly just for fun. Below is our list of films:

1921- The Sea Lion

1926- The Black Pirate

1933- In the Wake of the Bounty

1935- Captain Blood

1935- Phantom Ship

1936- Captain Calamity

1938- The Buccaneer

1939- Mutiny of the Elsinor

1940- The Sea Hawk

1942- The Black Swan

1948- The Pirate

1950- Buccaneer’s Girl

1950- Double Crossbones

1952- Against All Flags

1952- Blackbeard the Pirate

1952- Mutiny

1952- Pirate of the Blackhawk

1952- Yankee Buccaneer

1953- Peter Pan

1955- Long John Silver

1956- Manfish

1956- The Buccaneers (The Complete Series)

1982- The Pirate Movie

1987- The Princess Bride

1991- Hook

2003- Peter Pan

2003- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl

2004- The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou

2006- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest

2007- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End

Wednesday, June 10, 2009

Happy Rhode Island Anarchist Pirate Day!

Today is a very important day in Rhode Island history, because it commemorates the occasion 237 years ago when a bunch of Rhode Island nuts totally stuck it to the man and shot a British captain, IN THE GROIN, with a musket ball. (Then they burned his ship down.) It was among the very first incidents of truly violent colonial insurrection against the British, and of course the attack on the British trade-monitoring schooner Gaspee was led by a band of piratical (and likely drunk) Rhode Islanders who were just sick of having some Teabag all up in their business, inspectin’ their cargos for contraband.The full article is available here. Some more scholarly information on the Gaspee and the events surrounding its attack is available here.

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Mamas, don't let your babies grow up to be pirates

The 40,000 people who live in camps like 100-Bushes across Puntland have drifted in over the years, seeking refuge from the apocalyptic horrors in southern Somalia - civil war, drought and famine. Out here, there are no jobs. Only one in three children are in school, and the future for most is anything but promising.Mumena Abdur Qadir's worry is valid, as a recent Reuters article discussing Somali perceptions of piracy indicates:

No wonder then that mothers like Mumena Abdur Qadir are worried about their children - either that they will end up just as poor and destitute as their parents or that they will become pirates. "They drive around in expensive cars, they offer our sons lots of money, so of course piracy is an exciting option," she says. "But nobody likes them any more, and now it's really dangerous. The (French and the Americans) have been killing pirates, so we think it's a really bad thing to do."

Abdihafid, 13, dropped out of school, ran away from home and has taken up chewing khat and smoking cigarettes like the many brigands he sees in Hobyo."I want to be a commander of a pirate group," he said. "I know I am far too young, but I will wait until the right time."The Reuters article also discusses the, well, romantic implications of the romanticization of piracy, echoing earlier reports on pirates' sex appeal:

An extravagant convoy of forty 4x4s and four motorbikes escort a young bride to her nuptials at a sandy beach in the Somali village of Hobyo and are used to light up the twilight celebration.Her pirate commander groom has no eye patch -- but a sword and knife hanging from his belt do create a swashbuckling effect. "I am proud to be the leader's wife," said Sahra ... [L]ocal girls are finding it hard to resist the monied pirates. "I don't want to marry a pirate but time is flying and pushing me to have a pirate boyfriend because he is rich," said Halima, who at 24 is considered a bit too old to be single.According to the BBC article, Abdifatah Hussein Mohamed, an activist with the Puntland Students' Association, objects to this idealization of piracy and has been working hard in the region to convince other young people to just say no to piracy by deliberately reshaping the image of a Somali pirate:

When they began, Somalia's pirates cast themselves as "Robin Hoods of the sea" - as defenders of the nation's fisheries, first chasing away and later capturing foreign trawlers that had been looting the country's rich and unpoliced seas. Much of the money they took as "fines" went back into local schools, hospitals and businesses. No longer.As the article notes, however, rhetorically and socially isolating pirates is not likely to solve the problem on its own. International efforts are needed, and while many international associations (most recently the G8 and the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, which comprises the US, the UN, the EU, and NATO) have agreed with the need to coordinate responses, the Puntland administration maintains that working with the transitional federal government in Mogadishu is, for obvious reasons, unlikely to have much effect:"They're responsible for so many problems," said Abdifatah Hussein Mohamed. As an activist with the Puntland Students' Association, Abdifatah and his friends have created a multi-media empire. From their stuffy, cramped headquarters in central Bossasso, they churn out TV programmes, radio shows, magazines and websites with a single, simple message - piracy is out.

"First, they are responsible for inflation," he complained. "Now, food, land, cars are all too expensive for ordinary people. It used to be that you could hope for these things, but not any more. Then, they bring in prostitutes, they take drugs, they crash their cars. They rape whoever they want and nobody can do anything about it. Nobody wants them around any more."

His friend, Mohamed Jama agreed: "They are causing a lot of problems in the family. Sometimes women go with them because they promise lots of money. But they also divorce their wives very quickly too. It's bad for everybody."

And while both the US and the international community are claiming (limited) success in the war against piracy, this report from the Christian Science Monitor indicates that piracy continues to be profitable. If it's any consolation to the US Navy (here is an in-depth if slightly sprawling analysis of the modern role of the Navy in a purportedly post-naval era), anti-piracy efforts in the Straits of Malacca appear to be working, though as Elizabeth Dickinson points out, these successes are unlikely to be repeated off the Horn of Africa:"So many governments promised to help fight piracy on land, and that's a good thing," [President Abdirahman Mohamed Farole] said. "But they are all talking to the central government in Mogadishu. That's a policy decision, but it is a waste of time.

"The TFG (transitional federal government) only controls a piece of Mogadishu. They have no authority up here. So the rest of the world has to recognise that there are two legitimate governments in northern Somalia - Puntland and Somaliland - and deal directly with us if they want anything done."

First, none of the countries in the Pacific are failed the way Somalia is -- meaning that the countries could also combat the core of the problem on land, without fearing a "safe haven" ashore. Not so in Somalia, where pirate havens are essentially untouched.Except, perhaps, from a small, student-led group of anti-piracy activists, whose concern with the perception of contemporary piracy goes well beyond our own academic puzzlings. We wish them the best of luck.Even more important, while lots of countries want piracy in the Gulf of Aden to stop, no one or two of them are at such peril that they want to invest the resources to get the job done. In the Pacific, the three countries' economic survival as port hubs depended on their safety. No such pressure in Somalia.