Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Cutthroat Capitalism: too soon?

In the Wired game, you are a pirate captain in the Gulf of Aden, sailing around and attacking different vessels. After a successful attack, you are supposed to negotiate for the release of the ship and hostages by choosing different tactics that include beating and killing your hostages to prove to the pirate negotiator you are serious about your demands. If you "successfully" negotiate, you are allowed to go back to roving the high seas. There are no EU or NATO ships, monsoon weather patterns, or possibilities for shipwreck and drowning in the game, and while not all attacks are successful, every vessel is presented as a potential target.

It's probably a testament to my incredibly limited experience with computer and video games that it took me six or seven negotiations before I overcame my squeamishness about clicking "beat" or "kill" as a negotiation tactic even for purely experimental purposes, but even without doing so, the whole game seemed more than a little sick to me. (Notice to potential voters in the incredibly unlikely event I ever run for anything ever: I do not think playing violent video games makes you a bad/evil/violent person.) So why am I perfectly happy to fire cannons at the bad guy pirate LeChuck in the Monkey Island game and so incredibly uncomfortable hijacking colored dots in the Cutthroat Capitalism game? The obvious difference has to do with the tone of the two games: Monkey Island is silly while Cutthroat Capitalism is deliberately realistic in approach (if not in graphics). Although both actions are something pirates "actually do/did," Somali piracy has yet to be tempered with that temporal distancing that we have identified as a condition of possibility for the romanticization of Golden Age piracy. Until this happens, I suspect the game will continue to feel a bit "off" to me, though judging from the comments posted below the game, this is not the case for many people who have played it.

That the game would involve acting as a pirate rather than as a US Navy SEAL or a NATO commander was equally puzzling to me, since first of all, there's precedent for this kind of thing and second, increases in piracy have historically resulted in nationalist opposition to the threat. Indeed, there is plenty of evidence that this happened when the Somali pirates hijacked the Maersk Alabama, Captain Phillips and the Navy SEALS were frequently described as heroes, and the media response was quick to draw upon the "pirate-fighters as patriotic heroes" commonplace we identified as prevalent in the early 1800s, with TV shows and movies featuring the Somali pirates as the villains. I think a possible answer to this puzzle is that the "pirates as cool and edgy" and "pirates as free from the constraints of society" commonplaces that coexist today alongside the "pirates as a security threat" have created conditions of possibility for the appeal of this game, since they have opened up a space in which pirates can be protagonists -- and enviable ones at that. If this is indeed the case, "Cutthroat Capitalism" is a telling example of how our perceptions of contemporary piracy are shaped by historical representations, since I do not think that this game (or a non-electronic version of it) could have enjoyed the same popularity before piracy came to be seen as a purely historical phenomenon.

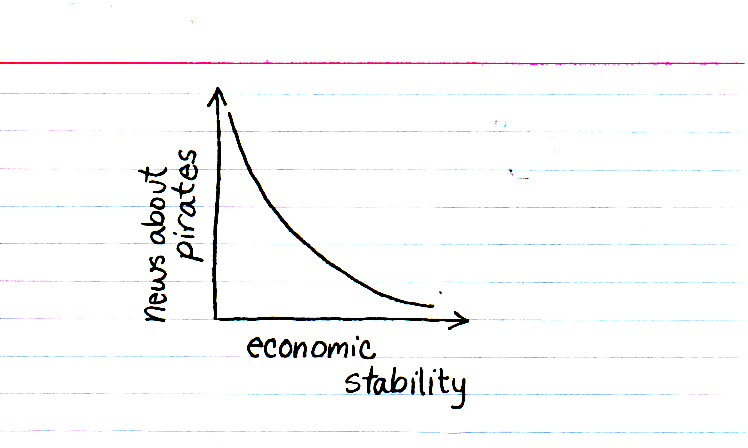

If a picture is worth a thousand words, we've already written an article!

My, uh, artistic endeavors tend to feature geometric shapes and arrows with not infrequent forays into the Cartesian coordinate system, and even when color is involved, the result is something like this:

So when my mildly awe-inspiring friend Fletcher generously offered to make the header thingy for this blog look much cooler, there was really very little reason not to accept. I would also like to take this opportunity to tell you to read his blog, Orbital Eccentricity, as it also features an aesthetically pleasing header, in addition to thought-provoking and insightful commentary on space policy legitimation.

Sunday, July 26, 2009

That thing you've been waiting for? It'll happen today!

THE LIST!

The pirate as ...

1. uncivilized, savage, lawless (modern version: piracy as a result of weak or failed states)

2. evil, sinner, against divine law

3. hostis humani generis/enemy of all mankind

a. active form (pirates declare themselves as such)

b. passive form (pirates declared as such by others)

4. Romantic protagonist

5. fictional villain

a. really actually very evil (PG-13, R)

b. Capt. Hook (PG, G)

6. practical (not moral) problem

a. strictly legal

b. negative externality as relates to trade and commerce

7. cool, edgy (Jack Sparrow, ambiguous morality)

8. absolutely harmless (Sesame Street fare)

9. tool of nationalism

a. hero (English, American, French)

b. villain (Spanish, English, American)

10. (inter)national security threat (pirate-terrorist conceptual nexus)

11. Goth/counter-culture symbol

12. libertarian wet dream

13. sex symbol

14. temporally/spatially distanced from the here and now

15. excessively violent actor (torture, murder, rape, etc.)

The list is in no particular order. It is worth noting that Catherine and I have adopted the numbers as shorthand for these commonplaces. Our conversations these days sound like this:

"There's definitely some '1' in this trial transcript, don't you think?"

"Yeah, plus that's an explicit reference to '3b' in the second paragraph."

"Sure but it's refuted by a deployment of '6a'."

"Beautiful! That explains the odd lack of '15' except by negation."

*ha. But we do have a considerable and comprehensive if not completely exhaustive amount of empirical and original archival research to back up this list.

Pirates in church?

Please Call Me By My True Names

Do not say that I'll depart tomorrow

because even today I still arrive.

Look deeply: I arrive in every second

to be a bud on a spring branch,

to be a tiny bird, with wings still fragile,

learning to sing in my new nest,

to be a caterpillar in the heart of a flower,

to be a jewel hiding itself in a stone.

I still arrive, in order to laugh and to cry,

in order to fear and to hope.

The rhythm of my heart is the birth and

death of all that are alive.

I am the mayfly metamorphosing on the surface of the river,

and I am the bird which, when spring comes, arrives in time

to eat the mayfly.I am the frog swimming happily in the clear pond,

and I am also the grass-snake who, approaching in silence,

feeds itself on the frog.I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones,

my legs as thin as bamboo sticks,

and I am the arms merchant, selling deadly weapons to

Uganda.I am the twelve-year-old girl, refugee on a small boat,

who throws herself into the ocean after being raped by a sea

pirate,

and I am the pirate, my heart not yet capable of seeing and

loving.I am a member of the politburo, with plenty of power in my

hands,

and I am the man who has to pay his "debt of blood" to, my

people,

dying slowly in a forced labor camp.My joy is like spring, so warm it makes flowers bloom in all

walks of life.

My pain if like a river of tears, so full it fills the four oceans.Please call me by my true names,

so I can hear all my cries and laughs at once,

so I can see that my joy and pain are one.Please call me by my true names,

so I can wake up,

and so the door of my heart can be left open,

the door of compassion.

I don't actually like the poem very much, but I have included it here as an example of a contemporary deployment of the "pirate as ultimate evil/hostis humani generis/enemy of all mankind" commonplace. That this common understanding of pirate is, to varying degrees, deliberately contested and refuted, both in the poem and in the wider context of the sermon, is actually further evidence of its being a rhetorical commonplace: In Civilizing the Enemy: German Reconstruction and the Invention of the West, Patrick Thaddeus Jackson takes great care to establish that a rhetorical commonplace is only weakly shared; it is a "potential resource," and "not a univocal, completely fixed bit of meaning that is identically possessed by multiple people; that would be a strong form of shared meaning, and ... would also have the logical consequence of making debate and discussion unnecessary: if we already agreed in this strong sense, why would we have to talk about it?" (28; 44; 50). Indeed, the sort of contentious conversations about representations of actors that Charles Tilly talks about in Stories, Identities, and Political Change are only possible with what he calls a shared set of idioms and history (116-118). Using pirates to demonstrate the possibilities of human compassion is an attempt to redefine the meaning of pirate, but such redefinition is only possible given that "pirates as evil" is already weakly shared among the congregation.

I feel like T-Rex explains this concept pretty well. (click to enlarge)

Saturday, July 25, 2009

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

Research trip, part VI: Harry Potter and International Relations

As Catherine noted some time ago, this project draws upon, among other analytical tools, the theoretical approach of popular culture as constitutive that is articulated in the introduction to Daniel Nexon and Iver Neumann's Harry Potter and International Relations. Primed as I was by a midnight showing of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince at the Morehead City, NC cinema, I decided to read it was my turn to read HP and IR on the train ride back to DC. One can only spend so much time pretending that the Carolinian is the Hogwarts Express, after all, especially as Amtrak refuses to serve pumpkin juice and chocolate frogs in its snack car. My reading generated the following uh, articulation of righteous indignation, posted here as I am not sure what else to do with it. Caveat lector: There are virtually no pirates whatsoever in this post.

***

For the record, I do not automatically critically object to everything I read, my comments regarding Peter Leeson's op-eds, Janice Thomson's footnotes, and deconstructionism notwithstanding. In fact, I thoroughly enjoyed many of the chapters in Harry Potter and International Relations, especially Ann Towns and Bahar Rumelili's chapter on the reception of Harry Potter in Sweden and Turkey; Maia Gemmill and Daniel Nexon's chapter on the religious politics of Harry Potter; Iver Neumann's chapter on the mythical geography of the magical world; and Martin Hall's chapter on mythology as methodology. However, Jennifer Sterling-Folker and Brian Folker's chapter, "Conflict and the Nation-State: Magical Mirrors of Muggles and Refracted Images," got my goat.

Setting aside for a moment the theoretical conclusions they draw by equating the conflict with Voldemort with a nationalist war, my first gut-level reaction to the chapter concerned the authors' unqualified use of the term "mudblood" to describe Muggle-born wizards (117). As anyone who has even skimmed Chamber of Secrets ought to know, "mudblood" is an incredibly derogatory term in the wizarding world, inciting a violent response from the entire Gryffindor Quidditch team when Malfoy uses it against Hermione. There are numerous other examples of the non-neutral connotations of the term from Snape's calling Lily Potter a mudblood in a remembered scene in Order of the Phoenix (a key plot point) to its wide-spread use in the Ministry of Magic after Voldemort seizes control of that particular state institution (more on that later). The obvious equivalent in the muggle world is, of course, the word "nigger," and the parallel becomes particularly acute with Hermione's bold and deliberate reappropriation of the term in Deathly Hallows.

It is odd, then, that not only do the authors cavalierly use the word "mudblood" when "Muggle-born" is clearly the appropriate term within the fictional social context the authors are analyzing, but they go on the explicitly equate the widely-used and value-neutral term "Muggle" with "nigger" (119). While I will grant that wizards often take a paternalistic tone in describing Muggles (and a downright evil one in the 7th book, though the authors could not have known that when writing the chapter, of course) the term "Muggle" itself is widely used by good and evil characters alike in the wizarding world. Indeed, the paternalistic tone the authors refer to is, I would argue, a deliberate literary device that adds some humor to the books (Mr. Weasley doesn't know how electricity works! Archie can't figure out the vagaries of Muggle dress!) and even a way to get young muggle readers thinking critically about their own taken-for-granted cultural norms in the tradition of "Body Ritual Among the Nacirema." Hermione, who clearly loves her parents very much, refers to them as Muggles; Hogwarts offers a class in Muggle Studies; the pre-Thicknesse Ministry of Magic had departments with "Muggle" in the name; even Dumbledore, the embodiment of goodness, talks of Muggle knitting patterns. Indeed, the lack of another term for non-wizarding humans points to the innocuous ubiquity of the term "Muggle." In short, there is nothing to support the authors' statement that "Muggle" is in any way a derogatory term.

These are two fundamental errors of empirical analysis in this chapter of Harry Potter and International Relations. There is no real question of interpretation here; while the precise wizard-Muggle relationship is debatable, that "mudblood" is "a disgusting thing to call someone" and "a really foul name" is not. This type of misreading has two implications: First, it seriously detracts from the authors' credibility in their analysis of Harry Potter and international relations. Either they did not read the books at all and relied instead on secondary sources, or their reading was superficial and ignored the nuances of wizarding social identities. My insistence on this seemingly small linguistic point may sound laughably nerdy and pedantic -- and indeed a social science analysis of a transparently constructed fictional world is always going to be subject to that sort of critique -- but the authors' decision to treat the world of Harry Potter as worthy of academic analysis effectively moots such critiques in this debate. I also felt this misuse of terms detracted from the overall credibility of the book; that sort of misreading should have been flagged by an editor or reviewer. Since the editors of the book were clearly targeting a Harry Potter-literate audience, they should have known to hold their contributors to the same standard.

The second implication of this linguistic imprecision is that it is indicative of a deeper misreading of the Harry Potter texts. Chief among these is the authors' equation of the wizarding world's conflict with Voldemort with identity-based (nationalist, religious, ethnic) conflict in the Muggle world. The authors argue that the fundamental difference between the liberal IR fantasy of the wizarding world and the realist reality of the Muggle world is that in the wizarding world power inheres to the individual and therefore the need for collective action is minimized. The authors' then state that there should be "relatively little cause for collective conflict among wizards and witches themselves as a result," and use this as evidence of the logical inconsistency of Rowling's "ultimate fantasy of liberal philosophy." They are correct in stating that there should be little collective conflict; in fact, there is not.

The problem lies not in Rowling's logic but in their reading of Voldemort's war against elements of the wizarding community as a collective conflict, on par with the Nazis' quest for racial purity. There are parallels, to be sure, and the Harry Potter series is nothing if not a call for greater tolerance in the world, but Voldemort's primary concern is not with creating an exclusively pureblood race (Voldemort himself is a half-blood). While blood purity is certainly the goal of the Death Eaters whose service he needs, Voldemort himself is obsessed with becoming the greatest wizard of all time by overcoming death. (In Rowling's fictional universe, it is occasionally possible to determine a character's motivations directly, but even without relying on a motivational account for Voldemort's actions we can conclude that the image he has crafted for himself is that of a wizard obsessed with power at all costs). The conflict in the Harry Potter series is not between purebloods and half-bloods (in any case, that only starts to become the case in the 7th book, which the authors did not know about); it is between Harry and Voldemort. It is a highly individualized conflict and whether or not that is a liberal fantasy, it is emphatically not an identity-based conflict in the model the authors envision.

The authors' concluding point is that the wizarding world has no link between identity and collective political structures, and this is why Voldemort and the Death Eaters never make an attempt to "seize the reins of power that the state embodies." But if the conflict in the series is read as something other than a collective identity-based movement, there is no immediate need for its instigators to gain state control. It seems to me that a more apt reading of the conflict is that of a lone wolf terrorist or a small guerilla movement that is intent on achieving a deluded, highly individual goal or acquiring power with no wider social agenda. This does not imply that Voldemort's actions do not have broader societal implications; because he does not care who gets hurt in his pursuit of power and because a climate of fear only makes his exercise of power easier, many, many people can and are maimed, killed, and tortured along the way.

The authors of the article write that "the seizure or control of the state is the means whereby muggle collectives can obtain goals such as racial purification and oppression that involve violence en mass [sic]" (122). But since racial purification and oppression are not Voldemort's chief concerns, except as means to an end, it makes sense that taking control of the Ministry of Magic would not be his primary goal, particularly since, as the authors note, the Ministry has only limited power in the wizarding world anyway. Here is where the inevitable and admittedly mediocre pirate reference comes in: desperate for to obtain some sort of power (at least of the economic flavor) but largely unconcerned by larger identity-based social concerns, the Somali pirates are not targeting the incredibly weak Somali government or any government at all. I do not in any way want to equate the Somali pirates with Voldemort's evilness; I merely wish to point out that targeting the state is not always the best way to become powerful, especially when you are starting from ground zero.

Ultimately, of course, Voldemort and the Death Eaters do gain control of the Ministry through holding Thicknesse under the Imperius Curse, literally turning the Ministry into a puppet government and the wizarding world into a police state, though -- in fairness -- the authors of the chapter could not have known this when they were writing. Once the wizarding world accepts that Voldemort is back, spreading fear is a good way for Voldemort to gain power, and control of even weak state institutions helps make this possible. That it would take so long for Voldemort to infiltrate the Ministry is thus indicative of the following: his primary concern with personal power and thus his relative unconcern for collective identity politics (personal power, at least in its early stages, does not require control of the state); the physical and social limitations of his power in the earlier books (does anyone really think Voldemort could infiltrate the Ministry of Magic when he didn't even have a body of his own?); and presumably also the fact that control of state institutions is a subject of little interest to most 10-14 year olds: the audience of the earlier books.

The broader point I wish to make here is that a cursory or incomplete reading of text to support a broader theoretical commitment fails at creating a compelling case on two levels: First, it destroys a scholar's credibility and authority on a given subject; and second, it leads to empirically flawed analysis that does little to support the theory in question. And on a much lower third level, it opens you up to criticism from 20 year-old IR students who grew up reading and re-reading the texts in question and do not like to see them carelessly wielded.

On that note, this quote from Dumbledore seems a particularly apt way to end this post, with its wonderful constructivist overtones* and its recognition the power of myth and story:

That which Voldemort does not value, he takes no trouble to comprehend. Of house-elves and children’s tales, of love, loyalty, and innocence, Voldemort knows and understands nothing. Nothing. That they all have a power beyond his own, a power beyond the reach of any magic, is a truth he has never grasped. (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, 710)*Dumbledore himself might be more of an interpretivist, however:

"Tell me one last thing," said Harry. “Is this real? Or has this been happening inside my head?” “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

Research trip, part V: North Carolina

Our trip to down to North Carolina was a pleasant change from the long days we spent overly air-conditioned windowless reading rooms on our earlier academic voyages. (Though as should be evident from the slew of posts below, I clearly have no shortage of affection for the resources such halls contain.) We traveled to Beaufort, North Carolina to talk to David Moore, an nautical archaeologist who is currently excavating Blackbeard's flagship the Queen Anne's Revenge and an expert on Blackbeard. Because the popular imagery and myths surrounding Blackbeard have exerted a considerable influence on contemporary conceptions of pirates and piracy, Blackbeard, like Buccaneers of America, makes a good case to trace through history.

We learned several interesting and significant things in the course of this interview, including changes made to the 2nd edition of Johnson's A General History of the Pyrates which point to increased dramatization of the subject matter. At one point, the first edition has Blackbeard marooning some men on an island with no inhabitants or provisions; in the second edition, this account has been embellished to say that there was neither bird, beast, or herb for their subsistence -- an unlikely story given the presence of fresh water on North Carolina's Outer Banks. Even Johnson's famous description of Blackbeard indicates considerable dramatic excesses:

So our Heroe, Captain Teach, assumed the Cognomen of Black-beard, from the large quantity of Hair, which, like a frightful Meteor, covered his whole Face, and frightened America more than any Comet that has appeared there a long Time. This beard was black, which he suffered to grow of an extravegant Length; as to Breadth, it came up to his Eyes; he was accustomed to twist it with Ribbons, in small Tails, after the Manner of our Ramilies Wiggs, and turn them about his Ears. In Time of Action, he wore a Sling overe his Shoulders, with three Brace of Pistols, hanging in Holsters like Bandaliers; and stuck lighted Matchs under his Hat, which appearing on each Side of his Face, his Eyes naturally looking fierce and wild, made him altogether such a figure, that Imagination cannot form an Idea of a Fury, from Hell to look more frightening.According to Moore, the only eyewitness account of Blackbeard is in Henry Bostock's deposition where the pirate is desribed merely as "a tall, spare man with a black beard which he wore very long." We were also intrigued to learn that Moore knows when a new Pirates of the Caribbean movie has been released based on the sudden spike in interest in his work, mainly among schoolchildren working on history projects. He also equated the enthusiasm and excitement surrounding the finding and excavating of the Queen Anne's Revenge with the similar emotions evoked by Pirates of the Caribbean, which indicates just how strongly the contemporary popularity of pirates is linked to their historical origins (however historically inaccurate current representations may be). Moore also kindly provided with an excellent annotated bibliography of primary and secondary sources on piracy, making note of the ones that had passed his litmus test of credibility by getting the sections on Blackbeard right.

The interview was productive, the North Carolina Maritime Museum both free and informative, and the free day we spent at the beach sunny and relaxing. We also took a great deal of delight in the pirate-themed atmosphere that pervades the town of Beaufort:

Monday, July 20, 2009

Research trip, part IV: Civil War-era pirates in Mystic

English Neutrality: Is the Alabama a British Pirate? (1863)

This pamphlet deals with the case of two Confederate ships, the Oreto (later the Florida) and the Alabama, both of which were built and anchored in Liverpool after Britain had declared its neutrality. However, the author of the pamphlet categorizes the neutrality declaration as an empty -- and in fact counterproductive -- move in terms of non-involvement in American hostilities:

Upon the breaking out of the rebellion, the British government made haste to concede belligerent rights to the insurgents, and to declare its intention to observe strict neutrality. The state of English law was such that this proclamation was entirely uncalled for, as it could neither increase nor decrease legal obligations or penalties; and its only effect was to guarantee to adventurers, who might wish to enlist with the rebellion, that they should thereby undergo no greater risks than the ordinary chances of regular war. The promulgation of the first proposition was generally taken to be, and perhaps was, intended to relieve such persons from the character and ugly responsibility of pirates and freebooters. It became, in fact, an invitation, as it did not, on the other hand, enjoin vigilance upon officials or threaten punishment to offenders.The question of whether or not these vessels, sailed as they were by almost exclusively British crews for the Confederate side, were pirates is a secondary one to the author of the pamphlet. He is much more concerned with documenting America's superior observance of the principles of neutrality when compared to Britain's allegedly profligate ways:

Thus stands the record of American neutrality. History may be fairly challenged to show another instance of such magnaminity, consistency, and fairness. Should we examine thoroughly the record of Great Britain upon this matter of maritime neutrality, it would be found entirely consistent on one point -- 'Britannia rules the wave.' To express the probable reasons for whatever inconsistencies on other points history might discover, would necessitate harsh allusions to that national greed and arrogance which the traditions of mankind have ascribed to that insular kingdom.Towards the end of a rather lengthy rant on American superiority, the author does address the question of piracy, as follows, concluding that the question hinges on the status of the Confederacy -- much as Tindall's 1694 analysis of the legal status of sea robbers holding letters of marque from a deposed king, James II, depended on the monarch's sovereign authority. This pamphlet concludes that the Alabama was a pirate, but with little analysis of the Confederacy's sovereignty, other than to make note of its not being recognized by other states:

The English sea-rovers claim, doubtless, to cruise under some kind of commission from the self-styled and unrecognized 'Confederate States.' I do not propose to discuss, with much seriousness, here, a question, which being in this place of little import, may hereafter, in a different discussion, become of the first magnitude; still, I am compelled to say that, by the law and practice of nations, it appears that no commission from an unknown, unrecognized authority can relieve the persons upon those vessels from the character of pirates ...The author concludes his essay, perhaps predictably by this point, with the following condemnation:

But, whatever may be the correct judgement on this point, one thing is certain, that all the character these vessels possess is British; and that if they are pirates at all, they are BRITISH PIRATES, roaming the seas, with the implied permission, if not actual connivance, of that government ...Interestingly, one of the exhibit halls within Mystic Seaport itself had a short display on the CSS Alabama, with a sign explaining that "Rather than pirates, most of the Alabama's officers were southern gentlemen and skilled naval officers..." While this line made me laugh aloud, it is interesting that even today, the utter incompatibility of the identities of "pirate" and "gentlemen" remains commonsensical.

United States vs. William Smith on charges of Piracy, Speech of Hon. William D. Kelley (1861)

If the author of the pamphlet on the Alabama was comfortable sidestepping the question of Confederate legitimacy, William D. Kelley clearly felt differently. In his speech of over 20 pages, Kelley devotes considerable time to berating the unconstitutionality, illegitimacy, and general traitorousness of the Confederacy. The case in question involved an American merchant schooner called the Enchantress which was boarded by a ship falsely flying the French flag in 1861. The defendant, William Smith, allegedly participated in capturing the crew and transporting them to Cuba to be sold as slaves, all the while carrying a letter of marque from the Confederate States. Kelley directly speaks to why such a letter does not make Smith a privateer:

But it is said ... that the Southern Confederacy is an existing government, fostering the arts and sciences, administering law, and having its own system of revenue and finance; that foreign nations long since recognized it as a belligerent power, and that its people have been treated as belligerents in our own civil courts; and can it not, you are asked, grant letters of marque? No, gentlemen, if all this be true -- and for argument's sake I admit it all -- it gives no validity to the letter of Mr. Davis. Letters of marque can only be granted by a member of the family of nations -- by a State whose national existence is recognized, and which as, or may have, diplomatic relations ... [W[hat nation has recognized the Southern Confederacy? None.But in addition to its head-on tackling of Confederate legitimacy, Kelley's speech is notable for several other reasons. First, it is one of the only legal documents I read (the other being the Savannah trial documents discussed below) which purposively eschewed applying the now-familiar hostis humani generis designation to pirates. Kelley deliberately sought to avoid the legal excesses that this term makes possible (see Jody Greene's "Hostis Humani Generis"):

The sole question for you to decide, I repeat, is, has this defendant been guilty of piracy under the laws of the United States, -- not under the common law, -- not is he the general enemy of the human kind, -- not has he the highwayman's heart and habits; -- but are you as a jury, satisfied that he has violated the laws of the United States for the prevention and punishment of piracy.Second, Kelley displays an acute awareness of the fuzziness of the "pirate" label, and pre-empts any possible defense that would invoke patriotic pirates like John Paul Jones. While his reasoning here is not particularly strong (it assumes the same jury would have convicted Jones on charges of piracy when the defense rests on the shared understanding that Jones was a Revolutionary War hero and not a pirate), that he rebuts this argument is indicative of the continued existence of acceptable non-fictional forms of piracy even into the mid-nineteenth century:

Is not Smith's case, you are also asked, precisely analogous to that of Paul Jones, and are you prepared to say that he should have been hung as a pirate? Let me answer that question, so adroitly put, by asking another. Is any one of the counsel for the defence prepared as a lawyer to say, that if before the recognition of our independence, Paul Jones had been taken on board a privateer by a British cruiser, the English law would not have condemned him as a pirate? The truth is, gentlemen, that Paul Jones, and all the American privateers of that day knew very well, that if they were taken, they would go into England and be tried for the crime of piracy.Third, one section of the speech has absolutely nothing to do with our pirate research project at all but is such a striking and beautiful example of American patriotism that, reading it as I did right after the Fourth of July, I felt the need to make it more widely known. Here 'tis, and a very belated Happy Independence Day:

And what defence is set up and how is it received? It is that this defendant was aiding the cause of those who are arrayed in arms against our brethern; that he was aiding the cause of those who thus punish our people for loyalty to their government; that he was aiding the cause of those who have stricken down and dishonored the flag of our country, and made war upon its institutions and people. And that defence is pressed and listened to, and weighed, and strengthened even by presumptions. It is right that it should be so. Such scenes as this, will redeem our generation in history. They prove that it is not our democratic republican institutions, that have begotten a tendency to barbarism among a people once civilized, generous, and humane; that the love of law and order, justice, truth and right, still dwells in the hearts of the American people, and are the sure pledge of the ultimate realization of the best hopes of those who have most faith in man's capacity for self-government.Trial of the Officers and Crew of the Privateer Savannah, on the Charge of Piracy, in the United States Court for the Southern District of New York. (1862)

The case of the Confederate privateer the Savannah is better known than the trial of William Smith, but much of the argumentation falls along the same lines (it is not surprising to find that Kelley references the Savannah case in at least one place in his speech). The library had the complete records of this trial, and while much of the several hundred pages of argumentation was long-winded and repetitive, the case really was a debate about what it is to be a "pirate" and was therefore absolutely fascinating, not to mention incredibly relevant to our project. On the matter of pirates as "enemies of all mankind," the District Attorney makes clear from the get-go that this is not the issue that the jury is asked to decide:

You have all, undoubtedly, heard more or less of the crime of piracy as generally and popularly understood. A pirate is deemed by the law of nations, and has always been regarded as the enemy of the human race, -- as a man who depredates generally and indiscriminately on the commerce of all nations. Whether or not the crime alleged here is piracy under the law of nations, is not material to the issue.However, immediately thereafter, the defense blatantly ignores this statement and frames the debate precisely in terms of popular understandings of piracy:

And when the first deed of wickedness has been done which makes pirates and outcasts of the men who perpetrated it, what is their career from that moment to the time when they end their lives, probably on the scaffold? Is it not one of utter disregard to the laws of God and man, and to those of humanity? Is it not a succession of deeds of cruelty, of rapine, of pillage, of wanton destruction? Who ever heard of pirates who, in the first place, commenced the execution of their design by public placards posted in the streets of a populous city like Charleston, approved of by their fellow citizens of a great and populous city, and not only by them, but by the people of ten great and populous States? ... the Jury must certainly have seen how utterly preposterous it is to characterize as piracy acts of this kind.The defense also evokes the spirit of John Paul Jones and the pirate heroes of the Revolutionary War, equating the crew of the Savannah with other, revered non-state actors:

But it is not necessary that the nation under whose commission he acts, shall be one which is already established and acknowledged among the family of nations. It may be a colony struggling for independence, and not yet recognized by the nations of the earth. Our own Courts years ago decided this case with a liberality which has eminently distinguished them, and established the principle in respect to the South American colonies -- colonies at that time not acknowledged by our Government as independent nations. So, gentlemen, it was with regard to the powers of Europe during the days of the American Revolution ... Their [American] letters of marque were recognized because they were the letters of a de facto Government ...At this point, the trial turns into an incredibly protracted (though certainly Civil War-defining) debate on the precise legal and sovereign status of the de facto Confederate government and whether or not it could issue letters of marque. That debate, while quite engaging, does not really bear further summary here.

A final observation I took from the Savannah proceedings was the direct use of popular narratives in the lawyers' argumentation. While the defense's allusion to popular understandings of piracy drew upon several of the pirate-related commonplaces discussed on this blog before (pirates as violent agents of destruction; pirates as outside both human and divine law), they also make direct use of narrative when quoting from William Wordsworth's poem "Rob Roy's Grave." As a brief contextualization of the quote, Wordsworth presents the highwayman Rob Roy as a Scottish Robin Hood (interestingly, the pirate-as-Robin-Hood defense is used today in the context of Somali piracy) who lives by no law but that "graven on my heart" (surely an allusion to a Rousseau-ian conception of natural law). The verse cited by the defense in the Savannah case is as follows:

For why? Because the good old ruleBut, intriguingly, rather than deploy this verse to equate the accused pirates with heroic Robin Hood figures, the defense uses the verse to show that the Savannah's crew are not pirates at all since they do obey a human law: that of the de facto Confederate government.

Sufficeth him: the simple plan

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can.

A Treatise of the Relative Rights and Duties of Belligerent and Neutral Powers in Maritime Affairs, by Robert Ward, Esq., Barrister at Law (1875)

If the intimate connection between fictional narrative and state policy regarding pirates seems weak in the Rob Roy/Savannah trial example cited above, the introduction to this treatise offers a true "smoking gun" example of the influence that popular culture can have on official policy. According to the author of the introduction, one Lord Stanley of Alderly, popular novels were directly responsible (or at least created the condition of possibility) for the delegitimation of privateering in England by equation privateering with the well-established evil practice of piracy. Here is Lord Stanley at his plummiest. It's a long excerpt, to be sure, but well-worth reading:

The prejudice against privateers arises partly from ignorance of the safeguards provided by the Law for the protection of vessels which are not lawful prize, and partly from the writings of officers of Royal Navies who have been unconsciously biassed by a prejudice similar to that which is felt by regimental officers against militiamen, volunteers, and irregular troops. The following is a passage taken at random, which may serve as a specimen of this kind of writing: 'There is but a slight step from the privateersman to the pirate; both fight for the love of plunder; only that the latter is the bravest, as he dares both the enemy and the gallows.' It was only after such sentences had been written, and the nation prepared by a course of such romance reading, that Lord Aberdeen told the people of Aberdeen that privateering was the last shred of barbaris, and that the only difference between a pirate and a privateer was that the latter bore the Queen's Commission. A similar comparison might be made between brigands and soldiers. If the subject had been studied in law books and not in novels, Lord Clarendon could not have based his attempted defence of the Declaration of Paris on the proposition that England obtained a valuable consideration for the acknowledged loss incurred by the giving up of her right to seize enemies' property in neutral vessels, by the abolition of privateering! The paragraph from a novel above quoted is followed by another, which shows how the false notions generally entertained on the subject of privateers, have been fostered by confounding the deeds done in former times with those done in the days of our grandfathers: 'But in whatever school they had been taught, the Buccaneers who kept about the English colonies were daring fellows and made sad work in times of peace among the Spanish settlements and Spanish merchantment.'" (vi-vii) [Emphasis added. The novel in question is Tales of a Traveller, by Geoffrey Crayon (Washington Irving), vol. ii. pg. 241)]Lord Stanley is, of course, violently opposed to the provision of the Declaration of Paris that outlawed privateering, calling it "the resignation of the means that had made England great and powerful." Undoubtedly his statement about the influence of novels is mildly hyperbolic but that he draws a direct connection between popular portrayals of piracy and something as undeniably "real-world" as the Declaration of Paris is very good evidence for the interconnectedness of cultural and legal understandings of piracy.

Research trip, part III: Fictional pirates in Mystic, CT

The first books I looked at in the Mystic Seaport library were a couple early editions of Treasure Island (first published in 1883), one from 1931 and one from 1949. The 1931 edition included a rather romanticized biography of Robert Louis Stevenson ("He inherited from his father a genial humor, a touch of Celtic melancholy, a sensitive conscience, a fondness for dogmatic statement, and a love for romance and for open-air activity; from his mother, a brilliancy, vivacity, and native grace, and a feminine sensitiveness to impressions; from her, likewise, a frail body and a predisposition to pulmonary disease, which he never outgrew, and which condemned him to a life of invalidism.") and also speculated as to popularity of Treasure Island at the time of its writing:

The major passion ... found little place in his stories; and his few women were not altogether satisfactorily drawn. For it was not love with its rewards and circumscribed plots and self-sufficiency that set best Stevenson's genius; but life with a hazard -- life kinetic under an open sky and on a broad field, full of struggle and "tailforemost morality"; life so circumstanced that the characters, driven forward through clean open-air adventure, act their parts in obedience to natural impulses and practical intelligence without the hesitations of conscience or the halting at questions of conduct ... Stevenson came at a time of 'spiritual fatigue'; when literature had lost much of its freshness and vigor, and was busy puzzling out the weightier problems of existence ... And the world, long since wearied by introspections and abstractions, was ready to turn away from gloomy forebodings to a more joyous mood.I'm not sure about the "spiritual fatigue" of the world, but certainly the association of pirates with a life of freedom from societal constraints has enjoyed long-standing popularity, manifesting itself today in insane libertarian schemes as those of the Seasteading Institute.

The early 20th century offered much in the way of speculation as to the popularity of pirates. Joseph Lewis French's 1922 introduction to Great Pirate Stories offers several interesting insights. The first of these is French's recognition of the important role temporal distancing plays in the romanticization of the men he himself calls savages:

There may be a certain human perversity in this, for the pirate was unquestionably a bad man -- at his best, or worst -- considering his surroundings and conditions, -- undoubtedly the worst man that ever lived. There is little to soften the dark yet glowing picture of his exploits. But again, it must be remembered, that not only does the note of distance subdue, and even lend a certain enchantment to the scene, but the effect of contrast between our peaceful times and his own contributes much to deepen our interest in him.A second point to take from French's introduction is that in the early 1900s, piracy was seen as an almost exclusively historical phenomenon:

It is said that he survives even today in certain spots in the Chinese waters, -- but he is certainly an innocuous relic. A pirate of any sort would be as great a curiosity today if he could be caught and exhibited as a fabulous monster.A final work of fiction worth mentioning was "The Pirate," published in an 1836 collection of stories entitled The Naval Annual: Or, Stories of the Sea. Both the description of the pirate ship and of the pirate captain (one Captain Cain) are indicative of the imagery associated with pirates at the time and that continues to hold sway. First, the description of the pirate ship the Avenger, which calls to mind Blackbeard's flagship, the Queen Anne's Revenge, both in name and insofar as it is a former slaveship:

Alas! she was fashioned, at the will of avarice, for the aid of cruelty and injustice; and now was even more nefariously employed. She had been a slaver-- she was now the far-famed, still more dreaded, pirate schooner, the 'Avenger.' Not a man-of-war which scoured the deep but had her instructions relative to this vessel, which had been so successful in her career of crime -- not a trader in any portion of the navigable globe but whose crew shuddered at the mention of her name, and the remembrance of the atrocities which had been practised by her reckless crew. She had been every where -- in the east, the west, the north, and the south, leaving a track behind her of rapine and murder.If the description of the ship likely drew upon the QAR, it's not hard to see traces of the following description of Captain Cain in Errol Flynn's 1935 silver screen portrayal of Captain Blood (disregarding the beard, of course, about which I imagine Jutta Weldes would have something to say):

In person, he was above six feet high, with a breadth of shoulders and of chest denoting the utmost of physical force which, perhaps, has ever been allotted to man. His features would have been handsome, had they not been scarred with wounds; and, strange to say, his eye was mild, and of a soft blue. His mouth was well formed, and his teeth of pearly white; the hair of his head was crisped and wavy,, and his beard, which he wore, as did every person composing the crew of the pirate, covered the lower part of his face, in strong, waving, and continued curls. The proportions of his body were perfect; but, from their vastness, they became almost terrific. His costume was elegant, and well adapted to his form: linen trousers, and untanned yellow leather boots, such as are made at the Western Ilser; a broad-striped cotton shirt; a red Cashmere shawl round his waist as a sash; a vest embroidered in gold tissue, with a jacket of dark velvet, and pendant gold buttons, hanging over his left shoulder, after the fashion of the Mediterranean seamen; a round Turkish skull-cap, handsomely embroidered; a pair of pistols, and a long knife in his sash, completed his attire.

Research trip, part II: The BPL, continued

Buccaneers of America aside, one of my most interesting finds at the lion-guarded BPL was a 1726 publication entitled A Discourse of the LAWS Relating to Pirates and Piracies, and the Marine Affairs of Great Britain. This was one of the few documents we've come across that offers an explicit definition of piracy, which is, of course, very useful to tracking changing perceptions of piracy. The author of the booklet begins with the now-familiar exhortation of British maritime supremacy:

The Sea was given by Almighty God for the Use of Man, and is subject to Dominion and Property, as well as the Land … the Kings of Great Britain have a Right to the Sovereignty or Dominion of the British Seas … But if any Nation shall presume to deny it, and actually go about to dispossess the Crown of this undoubted Right, or shall usurp or incroach upon the British Sovereignty of the Seas, which it so highly concerns the Honour and Safety of the Nation to maintain; the Crown of Great Britain will, without a doubt, be never unprovided with a Fleet, nor backward of putting them to Sea, to vindicate the Right which all our Kings have insisted upon, which the Laws and Customs of this Kingdom have ratified and confirmed, and which all Foreign Nations have, one Time or other readily acknowledged.The introduction goes on to specify that piracy is a crime subject to universal jurisdiction by virtue of its well-documented, historically-evidenced heinousness:

Piracy and Robbery at Sea is an Offense of that Nature, and is so destructive of all Commerce between Nation and Nation, that all Sovereign Princes and States have thought it their Interest, and made it their Business, to suppress the same; this they have done from the Time of Minos King of Crete to this very Day, as it testified by most Historians.Finally, pirates are explicitly referenced as "enemies of all mankind" (hostis humani generis) and effectively dehumanized as follows:

A Pirate has been always deemed, by all civilized Nations, to be one who is a Rover and Robber upon the Seas; and Piracy is termed committing Robberies upon the Seas; and from the Nature as well as the Wickedness of the Offence, a Pirate is looked upon as an Enemy to all Mankind, with whom neither Faith nor Oath is to be kept; and in our Law Books they are term’d Brutes and Beasts of Prey; and it is allowed to be lawful for those who take them, to put them to Death, if they cannot, with Safety to themselves, bring them under some Government to be try’d.[As an interesting side note -- and perhaps a future blog post -- Matthew Tindall's fascinating 1694 Essay Concerning the Laws of Nations and the Rights of Soveraigns has this to say about the long-standing international legal norm of piracy as a crime against humanity: "Hostis Humani Generis, is neither a Definition, or as much a Description of a Pirat, but a Rhetorical Invective to shew the Odiousness of that Crime." This insightful observation was clearly still relevant in 1726, and as Jody Greene argues in "Hostis Humani Generis" (Critical Inquiry 34, Summer 2008: 683-705), remains so today. She writes, "Even if we cannot determine what precisely a pirate is, even if pirate is nothing more than a term of opprobrium, the place occupied by the pirate in legal discourse can nonethless produce measurable effects." Greene makes a comparison between the catachrestic historical usage of "hostis humani generis" and today's usage of "war on terror" as "endlessly generative fictions." While I don't completely agree with her comparison of pirates and terrorists -- even as legal categories (the idea that the terms are misapplied troubles me as it suggest there is an objectively "correct" application of these terms) -- her statement that the deployment of the term "pirate" creates observable conditions of possibility for state action is compelling and, I would argue, should be expanded beyond its narrow legal implications.]

But, I digress. The 1726 booklet in question goes on to document laws for punishing pirates and accessories to piracy; laws punishing ship capitains who fail to fight back against attacking pirates; laws rewarding commanders and officers for successfully defending their ships against pirate attacks (as the author notes, "In the time of King Charles II, it was common for masters and commanders not to fight back, even if they had sufficient force to defend themselves."); and laws against trading with pirates and receiving stolen goods; and laws aimed at deterring people from becoming pirates.

The conclusion of the pamphlet leaves little doubt as to the author's (rather non-legal) opinion of pirates:

It is a melancholly Consideration, that any of those Persons, who have given themselves over of late Years, to the committing of Robbery on the High Seas, should not have been content with taking what Money they have found, or Things they might stand in need of aboard of any Ship which has fallen into their Hands; but run into such Extravagancies, as to throw the rest of the Goods into the Sea, set fire the Vessels, and murder the Company, without any manner of Provocation, on the Part of those they have destroyed. This many of the piratical Crews have done, in cold Blood, and as if it were only for Pastime, and for their Diversion …This is followed by a lengthy religious condemnation of piracy, promising firey hell to sea robbers and concluding that "whosoever sheddeth Man’s Blood, by Man shall his Blood be shed."

A second, more entertaining find was the 1824 masterwork The Atrocities of the Pirates; being a Faithful Narrative of the Unparalleled Sufferings Endured by the Author during his Captivity among the Pirates of the Island of Cuba; with an Account of the Excesses and Barbarities of those Inhuman Freebooters. By Aaron Smith, (Who was himself afterwards tried at the Old Bailey as a Pirate, and acquitted.). Really, the title itself should be give you a pretty good sense of the general tenor of this, uh, faithful narrative, but in case there was any doubt, it is chock full of "horrid cruelties," "merciless monsters," brutal torture scenes, and an angelic Spanish maiden named Seraphina. Smith's physical description of the Pirate Captain offers clear evidence of the "pirate as uncivilized savage" commonplace that was so prevalent in the early 19th century:

He was a man of most uncouth and savage appearance, about five feet six inches in height, stout in proportion, with aquiline nose, high cheek bones, a large mouth, and very large full eyes. His complexion was sallow, and his hair black, and he appeared to be about two and thirty years of age. In his appearance he very much resembled an Indian, and I was afterwards informed that his father was a Spaniard and his mother a Yucatan Squaw.Smith's descriptions of the pirates' actions are similarly fraught with inhumanity:

I saw that his brutal temper was excited by this information; his eyes flashed fire, and his whole countenance was distorted. He vowed destruction against the whole party, and rushing upon deck, assembled the crew, and imparted what he had heard. The air rang with the most dreadful imprecations; they simultaneously rushed below and dragged the helpless wounded wretch upon deck, and, without taking into consideration that the accusation against him might be unfounded, proceeded to cut off his legs and arms with a blunt hatchet, then mangling his body with their knives, threw the yet warm corpse overboard.The doubtful historical accuracy of Smith's yarn aside, it is nonetheless a useful articulation of the popular mythicization of the pirate at the time of his writing.

And as a final note on the subject of pirates in fiction, the Mystic Seaport bookstore provided ample evidence of the enduring popularity of pirates in children's fiction: the legacy of works like Peter Pan and Treasure Island:

Research trip, Part I: Buccaneers of America at the Boston Public Library

Car on peut dire en passant qu’il [Exquemelin] n’avance rien dont il ne rende raison bien éloigné de la manière de certains Autheurs, qui reduisent ceux qui les lisent à deviner ou du moins à les croire sur leur parole.The translator's brief mention of the buccaneers themselves makes clear their heroic virtues:

[Incidentally, we note that the author presents nothing that is not grounded in reason, as opposed to certain other authors who force their readers to guess or even just to take them at their word.]

Il nous convainc encore par beaucoup d’exemples, de la valeur & de l’intrepidité de ces mesms Avanturiers, qui seulement avec des fusils, des sabres, & d’autres armes ordinaires, prennent des Navires, des Forts & des Villes, qu’on ne pourroit prendre qu’avec des Armées & des Sieges, qu’avec du Canon, des Mines, & d’autres moyens semblables qui sont d’un grand secours à la guerre …The illustrations of this edition stuck to this theme; whereas English-language editions from the same time period depicted almost exclusively the pirates featured in Exquemelin's account and their more memorable atrocities (sacking cities, cutting out people's hearts), the 1686 French edition included only three illustrations: one of a sea turtle being stabbed, one of what I think was a manatee, and one of a buccaneer roasting meat over an open fire. This edition also contained a beautiful fold-out map the Caribbean with a detailed map of Tortuga:

[Using numerous examples, he (the author) convinces us further of the bravery and intrepedness of these adventurers, who took ships, forts, and towns with only rifles, swords, and other small arms when they ought to have needed armies and sieges, cannons, mines, and other such arms of war.]

I also read a Spanish-language edition from 1793 (Piratas de la America y luz a la defense de las costas de Indias Occidentales) which was notable chiefly for its (predictable) nationalist appeal to the strength of Spain. As noted in the title, its brief translator's note includes a description of how the work will help Spain continue to defend its North American territories as well as several verses (the latter presumably written by the translator himself) highlighting Spain's brave and warrior-like fight against pirates:

Nunca el Leon se muestra temeroso,I also took a look at a 1931 Dutch-language edition of Buccaneers of America (De Americaensche Zeerovers). The introduction begins by noting the enduring popularity of the book, its many reprints and translations, and its influence on pirate and adventure stories, as well as the difficulty of tracking down the original:

Aunque tenga ventaja el enemigo:

Siempre Espana al Pirata cauteloso,

Aun rugiendo da horrífero castigo.

[The Lion never shows fear

Even if the enemy has the advantage:

Spain is always on guard, roaring against pirates,

Even when it brings about horrific punishments.]

and

Tú, ó Alonso, mas doctor y verdadero,

Descbribes del América ingenioso

Lo que asalta el Pirata codicioso:

Lo que defiende el Espanol guerrero.

[O Alonso, truthfully and wisely

Describe the America

That the covetous pirate attacked

And the Spanish warrior defended.]

Het boek, dat hier voor het eerst sinds 1709 herdrukt wordt, is de Hollandsche "oer-tekst" van het over de geheele wereld vermaarde werk, door Exquemelin over de bedrijven der vrijbuiters in de West-Indische wateren geschreven, een tot op heden nog veel gelezen, in de Fransche, Engelesche, Duitsche en Spaansche vertalingen nog steeds herdrukt avonturen-boek, dat in de latere jaren de stof heeft geleverd voor tallooze piraten- en avonturen-romans. De populariteit van dit boek maakte het des to opvallender, dat van de oorspronkelijke, door een Hollander in het Hollandsch geschreven uitgave, nog steeds geen nieuwe herdruk bestond, te meer waar die oorspronkelijke eerste uitgave vrijwel onvindbaar is geworden en slechts enkele bibliotheken ten onzent er een exemplaar van bezitten.The introduction goes on to attempt to figure out who Exquemelin really was and to document the history of the book's translations and reprintings. This edition included many illustrations, all done in a black-and-white cartoonish style that indicates that by 1931 in the Netherlands, pirates were well-established in the realm of children's stories and buffoonery (though it should be noted that the illustrations of Lolonois cutting out a man's heart and beheading captives aboard a ship remain thoroughly macabre):

[This book, which is reprinted here for the first time since 1709, is the Dutch "ur-text" which is known throughout the whole world, written by Exquemelin about the buccaneers of the West Indies, most often read until now in the French, English, German, and Spanish translations, and that in later years provided the material for countless pirate and adventure stories. The popularity of this book, written originally by a Dutchman in Dutch, makes it all the more surprising that there have been no recent reprintings. The original first edition has become almost impossible to find and only a few libraries have a copy of it.]

Finally, we took a look at a 1914 English-language edition of Buccaneers of America intended for a young audience, as the George Alfred Williams, the author of the introduction notes:

In arranging this edition, the original English text only has been used, and but a few changes made by cutting out the long and tedious descriptions of plant and animal life in the West Indies, of which Esquemeling had only a smattering of truth. But, the history of Captain Morgan and his fellow Buccaneers is here printed almost identical with the original English translation, and we believe it is the first time this history has been published in a suitable form for the juvenile reader with no loss of interest to the adult.As is so often the case in reprintings of Buccaneers of America, this edition too was at least partially motivated by current geopolitical events:

The world wide attention at this time in the Isthmus of Panama and the great canal connecting the Atlantic with the Pacific Ocean lends to this narrative an additional stimulus.The most striking elements of this edition, however, were the wonderful illustrations by George Alfred Williams, which appear to be strongly influenced by those of Howard Pyle and help show where modern ideas of what a pirate looks like come from: